A Mental Model for Google’s Titans: Memory as Weights vs. Memory as Buffer

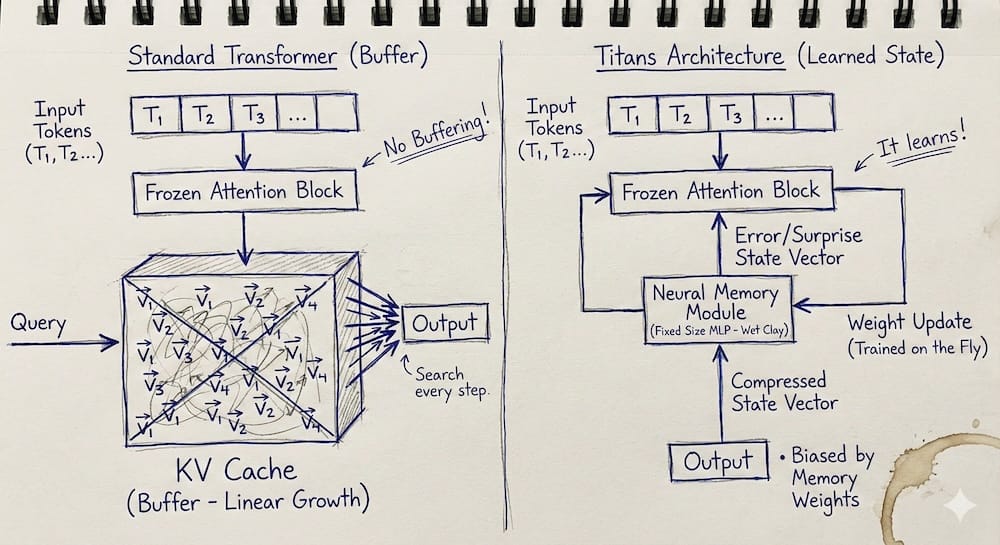

Most current Large Language Models (LLMs) handle long documents by increasing the size of their "context window." While effective, this approach has a fundamental scaling limitation. Google’s new Titans architecture (built on the MIRAS framework) proposes a different mechanical approach to memory.

To understand how it works, it helps to distinguish between two types of memory: Buffering (what Transformers do now) and Learning (what Titans introduces).

The Standard Approach: The Buffer (Attention)

In a standard Transformer, "memory" is essentially a temporary storage buffer (the Key-Value Cache).

- How it works: Every token the model reads is converted into a vector and stored in a growing list.

- Retrieval: When you ask a question, the model performs a mathematical search (attention) across this entire list to find relevant information.

- The Limitation: This is linear growth. To remember twice as much text, you need twice as much memory. It functions like a linear recording; nothing is prioritized until the moment of retrieval.

The Titans Approach: The Weight Update (Neural Memory)

Titans adds a secondary component called a Neural Memory Module. Unlike the buffer, this module has a fixed size regardless of how long the document is.

Instead of storing the data itself, it stores the patterns within the data by updating its own neural weights in real-time.

- How it works: As the model reads text, this memory module runs a continuous training loop. It attempts to compress the incoming information into its existing network.

- The Shift: It does not append new vectors to a list; it modifies the internal matrices of the memory module. The "memory" is no longer a retrieved file; it is a learned state.

The Determinant: "Surprise" (Gradient)

Since the memory module has a fixed capacity, it cannot learn everything with equal fidelity. It uses a "surprise metric" to determine what to prioritize.

- Prediction: The module attempts to predict the next piece of data.

- Error Calculation: If the prediction is accurate (Low Surprise), the model assumes the information is already represented in its weights, and little changes.

- Weight Update: If the prediction fails (High Surprise), it generates a large error signal (gradient). This signal forces a significant update to the memory module's weights.

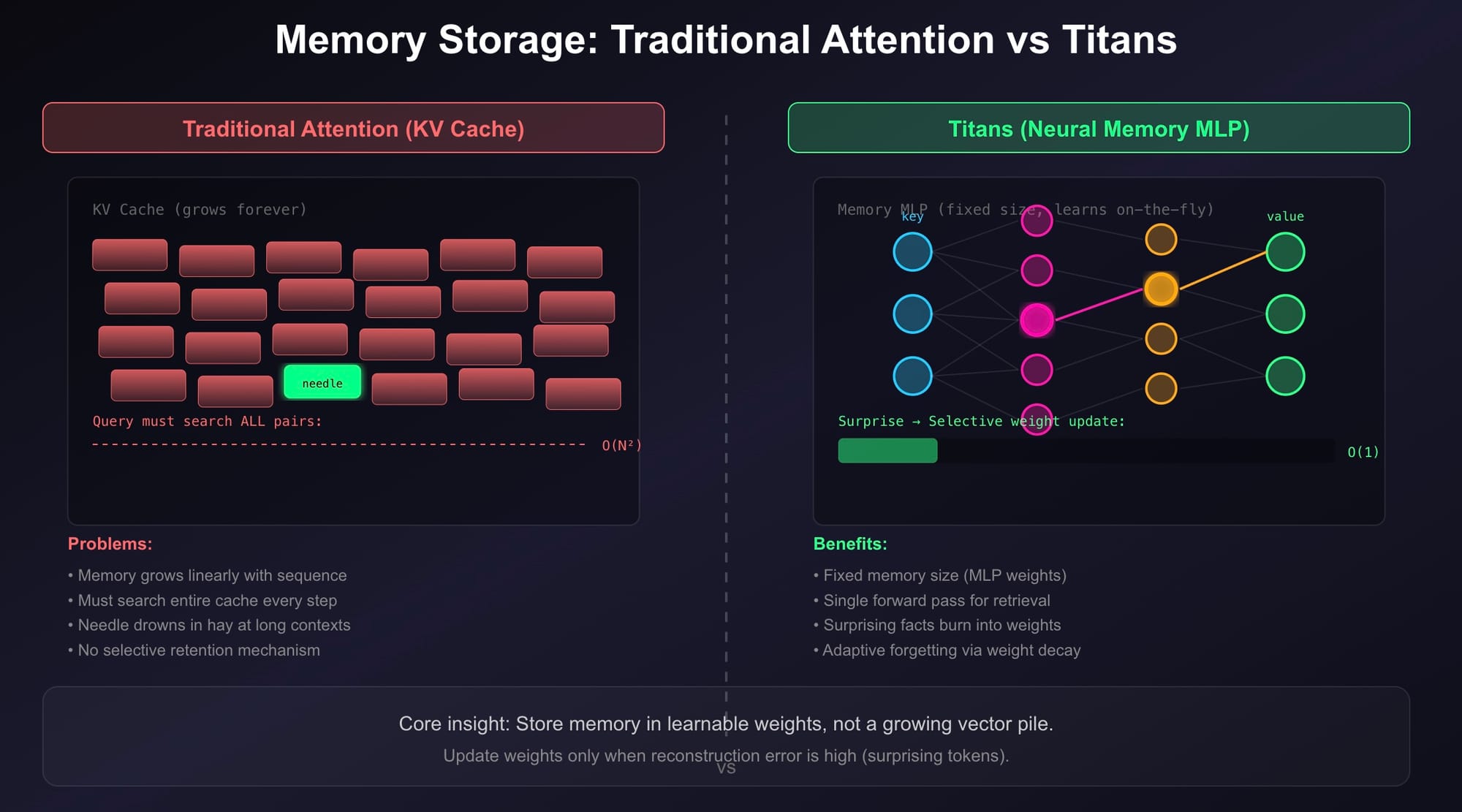

Why This Matters for "Needle in a Haystack"

Consider a scenario where a long financial document contains one anomalous sentence: "The CEO is a Martian."

- Standard Transformer: This sentence is just one vector sequence among millions. During retrieval, the model must successfully attend to this specific sequence amidst the noise of the rest of the document.

- Titans Architecture: Because this sentence is highly unexpected (high surprise), it triggers a sharp gradient update. The memory module’s weights are physically altered to accommodate this fact.

- Effectively, the model performs Test-Time Training on the anomaly.

- When the model later generates an answer, it isn't "searching" for the sentence. The "memory" of the CEO being a Martian is now part of the model's weight structure, biasing the output automatically.

Titans / MIRAS

Learning to memorize at test time via surprise-gated weight updates

Traditional Attention: The Hoarder's Dilemma

KV Cache Growth

Every token adds a KV pair. Memory grows linearly. At 2M tokens, you're searching through 2M vectors every step.

Quadratic Search Cost

Query must dot-product with every key. Finding one needle means touching all hay.

Attention is secretly trying to be a long-term memory system. But it stores memory in a growing garbage pile of vectors, then rummages through the entire pile every single step.

Like a hoarder who never throws anything away and has to search through mountains of junk to find one receipt.

Summary

The Titans architecture moves the mechanism of long-term context from storage to computation.

- Standard Attention: Keeps the history as a reference library (searchable, precise, but expensive).

- Titans/MIRAS: Digests the history as a learned state (compressed, abstract, and efficient).

By allowing the model to "fine-tune" itself on the prompt as it reads, it solves the haystack problem not by searching better, but by permanently (for that session) learning the needle.